“…and what with this and that we are frolicsome as the article on Natural History in the Daily.”

George Meredith

This is likely the only time you will see the skeleton of a monkey on my blog. He’s a cheerful looking fellow, to be sure, with that certain je ne sais quoi, and it remains to be seen if he belongs here–here in a post about natural history that is actually supposed to be about Victorian poet George Meredith. I liked him a great deal, though, and named him Dudley. (the monkey, not George).

This is likely the only time you will see the skeleton of a monkey on my blog. He’s a cheerful looking fellow, to be sure, with that certain je ne sais quoi, and it remains to be seen if he belongs here–here in a post about natural history that is actually supposed to be about Victorian poet George Meredith. I liked him a great deal, though, and named him Dudley. (the monkey, not George).

Rather warm and fuzzy for a skeleton, I thought…

‘Teach me to feel myself the tree,

And not the withered leaf.’ [George Meredith]

We might love nature, we might love history, but Natural History is another thing, altogether. I was reminded of this over the weekend.

Saturday was a brisk autumn day in downtown Portland, gorgeously clear and sunny. My husband and I were strolling through the university blocks of Portland State, my thoughts alight with all sorts of yummy dreamy snippets of literature, being surrounded, as we were, by old architecture, halls of learning, glistening trees, and the slow…slow…poetic float of falling leaves.

We soon found ourselves at the Natural History exhibit in the Science Building.

It was fascinating, but….a startling contrast to my previous perambulations. We went from glowing leaves and warm old brick in October sunlight to skeletons, dead carcasses, and dried feces of some sort at every display. Grim evidence of the food chain and our own mortality was suddenly everywhere. I do know what Natural History means, but I hadn’t quite prepared myself for the change in mood. Actually, it was great fun!

We saw, not just a skeleton of a zebra, but the skeleton of a zebra being pounced on by the skeleton of a lion. A strangely electric moment of both life and demise, sketched in one lyrical arc of calciferous white.

Rounding the corner we came across a reticulated python, which at first I confused with ‘articulated’ as he was quite dried out but still flexible enough in the joints to be woven back on himself several times over. I was trying to calculate his reticulations, just to see if I could figure out how long of a vermin-consuming monster he might have been in his younger days. However, my brain is not what it once was in my younger days–in this I shared a brief moment of sympathy with the python–and therefore calculating any sort of reticulation is not as easy as it sounds.

Oh, and those little tiny mouse paws under glass, severed from the body they once knew, still clutching a precious morsel of food… Possibly an al fresco lunch, gone horribly awry.

‘She realized she could skip lunch; suddenly even a light salad seemed excessively cruel.’

The grizzly skeleton was awesome to see, and I greeted him almost like an old friend. Ever since 1966, when I watched Night of the Grizzly and fell in love with Clint Walker I have been fascinated with tall, menacing grizzlies. And have declined the tent, while camping.

‘No thanks, I’ll take the cabin.’

Perhaps that movie scarred me–I don’t know. I just know I was happy to see a grizzly skeleton, and think of Clint Walker once again. Youthful crushes are never forgotten.

My brain can turn around just about anything to a ‘this is fascinating and I’ll tell you why’ level of interest, so naturally, in our little pop-up version of a Museum of Natural History, I began to think of Victorian writers. So many of our beloved poets and authors were naturalists, as well. Often they might spend a lifetime collecting dried out dead things and then, upon their own death, donating the lot to a museum (after having themselves properly buried, of course, because—who wants to look at THEIR skeleton?).

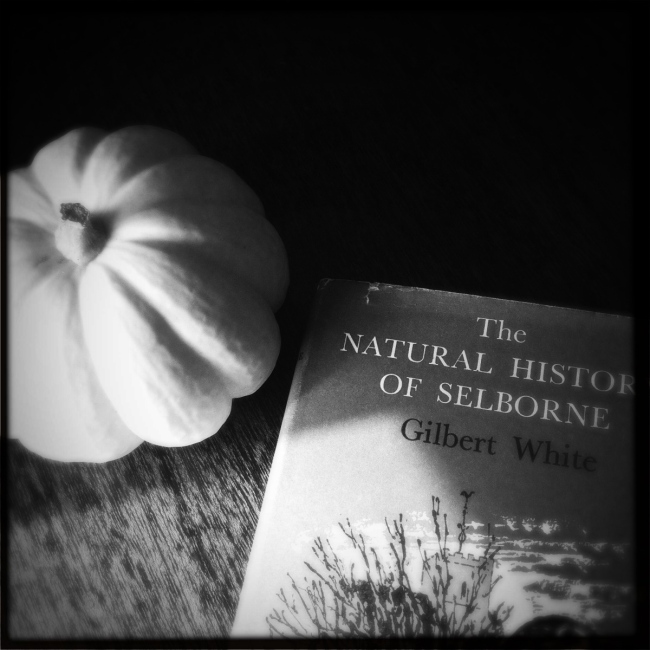

One of the most popular naturalists—pre-Victorian—is Gilbert White. His book The Natural History of Selborne, has outsold even the works of Jane Austen. However, as I have written enthusiastically of dear Gilbert more than once in these pages, I will content myself with just one tiny little quote, (okay two), that highlights his curious preoccupations and therefore mine:

‘A certain swallow built for two years together on the handles of a pair of garden-shears, that were stuck up against the boards in an out-house, and therefore must have her nest spoiled whenever that implement was wanted: and, what is stranger still, another bird of the same species built its nest on the wings and body of an owl that happened by accident to hang dead and dry from the rafter of a barn.

This owl, with the nest on its wings, and with eggs in the nest, was brought as a curiosity worthy the most elegant private museum in Great Britain. The owner, struck with the oddity of the sight, furnished the bringer with a large shell, or conch, desiring him to fix it just where the owl hung: the person did as he was ordered, and the following year a pair, probably the same pair, built their nest in the conch, and laid their eggs.

The owl and the conch make a strange grotesque appearance, and are not the least curious specimens in that wonderful collection of art and nature.’

Did I mention that Gilbert White has outsold Jane Austen? Oh, yes, I did…but I’m not sure how recent those calculations are, and if they were done before or after Jeremy Northam was cast as Mr. Knightley. This might have shifted the balance, being Natural History of a different sort.

On our tour, I was able to pet an owl’s wings, marvel at the downy undercoat, and closely examine a regurgitated pellet for exoskeletons. I felt very Gilbert White at that moment.

‘Selborne, May 7, 1779.

It is now more than forty years that I have paid some attention to the ornithology of this district, without being able to exhaust the subject: new occurrences still arise as long as any inquiries are kept alive.’

I truly believe that a lively curiosity keeps us young. By all means, let us ‘keep inquiries alive’! I should also mention the delightful and warm enthusiasm shown us by the science students who were hosting our tour. From antarctic mosses and their effect on global warming, to those aforementioned charming exoskeletons in owl pellets to ‘feeling’ how elephants communicate through the ground, at every display was a smiling face and a knowledgeable student eager to impart a love of the natural world.

I’ll leave you with another snippet of poetry from George Meredith. This is my year of reading George, so to speak. Perhaps he might enter these pages a bit more, and nudge out Gilbert in popularity. (ah, the silence which chirping crickets rush to fill!) As it turns out, he was a natural history enthusiast par excellence, and a tireless walker. I am enjoying, very much, his finely tuned ear for poetry, and his expressive love of the beauties of nature.

This poem, Autumn Evensong, is simply lovely. Enjoy…oh, and don’t give Dudley another thought. He’s quite happy, and has many admirers.

The long cloud edged with streaming grey

Soars from the West;

The red leaf mounts with it away,

Showing the nest

A blot among the branches bare:

There is a cry of outcasts in the air.

Swift little breezes, darting chill,

Pant down the lake;

A crow flies from the yellow hill,

And in its wake

A baffled line of labouring rooks:

Steel-surfaced to the light the river looks.

Pale on the panes of the old hall

Gleams the lone space

Between the sunset and the squall;

And on its face

Mournfully glimmers to the last:

Great oaks grow mighty minstrels in the blast.

Pale the rain-rutted roadways shine

In the green light

Behind the cedar and the pine:

Come, thundering night!

Blacken broad earth with hoards of storm:

For me yon valley-cottage beckons warm.